We should have seen this coming.

In the February, 1982 issue of National Geographic magazine, the cover was a photo that included images of the pyramids in Egypt. Just one problem. One of the pyramids was not where it was supposed to be.

Because the original photograph was shot horizontally, and the cover is vertical, the editors decided to move one of the pyramids graphically to fit that format. That did not go over well and their credibility was damaged. They apologized and pledged that they would never alter an image in their publication again.

But a new era had dawned. With the advent of software such as Photoshop, seeing was no longer believing as far as still images went.

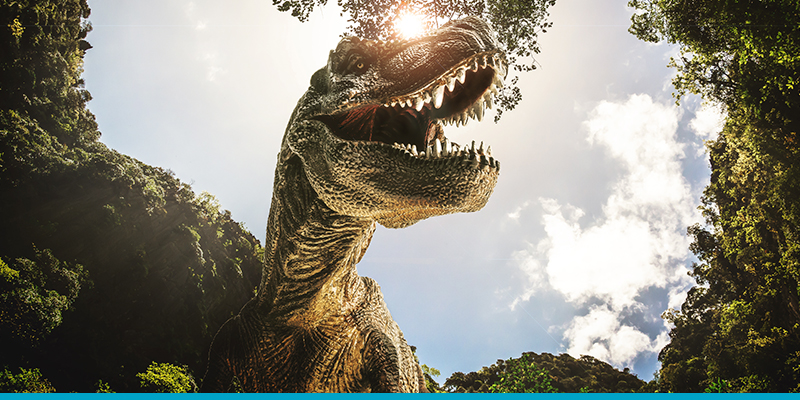

In the video world, manipulation of video images is connected to the increasing sophistication of computer-generated special effects. We all remember the tyrannosaur in Jurassic Park and how real it looked compared to the stop motion animation of the past. But did you know in one of the scenes, the jeep the t-rex was pushing around was also computer generated? For production reasons, they decided to digitally create a shot of the jeep rather than use the jeep itself. And you probably didn’t notice.

Move forward to one of the early Marvel blockbusters “Captain America: The First Avenger.” In the movie, they had to make Steve Rogers transition from a skinny kid in Brooklyn to, well, Captain America. They were able to digitally slim down Chris Evans’ face, and put on the body of a thin actor. The effect was pretty much seamless. Currently, production studios can create digitally-created worlds, creatures and even people that are photo-realistic.

In the video world, seeing is no longer believing.

And in the audio world, digital technology is also changing the believability landscape. Last year Jordan Peele, who does a very credible Barack Obama impression, and his production company worked with BuzzFeed to create a fake PSA using existing video of Obama edited to match Peele’s audio impersonation. It sure looked like it was Obama saying things he never actually said. We won’t provide a link due to language, but it is easy to find on your browser.

In this type of video, the current technology is more about making video morph to match a fake audio track. Audio engineers can do sophisticated edits to an existing audio track, appearing to make people say things they are not. While the technology is not quite perfect (yet), to create new words and sentences out of audio samples, editors can take existing video and digitally alter it to fit a doctored audio track- and still have it look like unedited video.

In the audio world, hearing is no longer necessarily believing.

We now have the term “deepfakes,” which refers to digitally-altered photos, audio and video to make scenes that never actually happened. While used to great utility in the movie, television and advertising industries, the implications for news and politics are profound, especially in the age of social media. In 2018, a video depicting House Speaker Nancy Pelosi slurring words was created from an existing video. In this case, the original video was shown next to the doctored video, exposing the deception.

Technology is being developed to help uncover whether digital media has been edited, but it is a continually whack-a-mole effort as more sophisticated editing software is being developed. The problem is not just that video and audio can be faked to appear real and cause confusion. Politicians who see an unflattering video of themselves can now say that the video was altered, and they didn’t say it. Proving a negative can be challenging under the best of circumstances.

So, at this time there is no easy solution other than we as media consumers and citizens need to be aware that this technology exists and is being used to manipulate us.

Or as Chico Marx said as Chicolini in Duck Soup: “Well, who ya gonna believe? Me or your own eyes?”

That question is now a lot harder to answer.

By Rich McEwen, Senior Associate